AI (in)Efficiency Revisited

Does Deepseek Change Any(every)thing?

In January of this year I posted an analysis of AI efficiency (or more properly, inefficiency) and several approaches to address those inefficiencies:

AI (In)Efficiency

When ChatGPT 3.5 came out, I heard two kinds of reactions. A friend told how impressed he was, and how it was better than several (human) interns he had in his work. Members of my family were alarmed, wondering if this was the start of an AI takeover.

Recently, however, the release of Deepseek has raised the question of whether the Chinese have solved the problem - Deepseek claimed performance as good or just slightly below that of frontier models while being vastly more efficient for both training and inference, costing under $6 million to train (see the Deepseek v3 Technical Report).

While the true cost of Deepseek has been seriously questioned (see, for example, the analysis from SemiAnalysis, but also by DeepSeek itself), DeepSeek has introduced a novel combination of approaches that singly were already being investigated but not combined, as well as implementation of some new ideas. This is a very high level overview - for a more detailed technical analysis, you might wish to see the series of blog posts DeepSeek Technical Analysis by Jinpeng Zhang.

In addition, researchers largely at Stanford University have, at about the same time, demonstrated a significant gain in inference/reasoning performance by implementing a form of test time scaling while using a very small, but carefully curated, sample test set (s1: Simple test-time scaling).

Do these advances solve, or promise to resolve, AI inefficiency?

Deepseek Architecture

Deepseek implemented, at a high level, two major approaches that are not new, but were done in an innovative way.

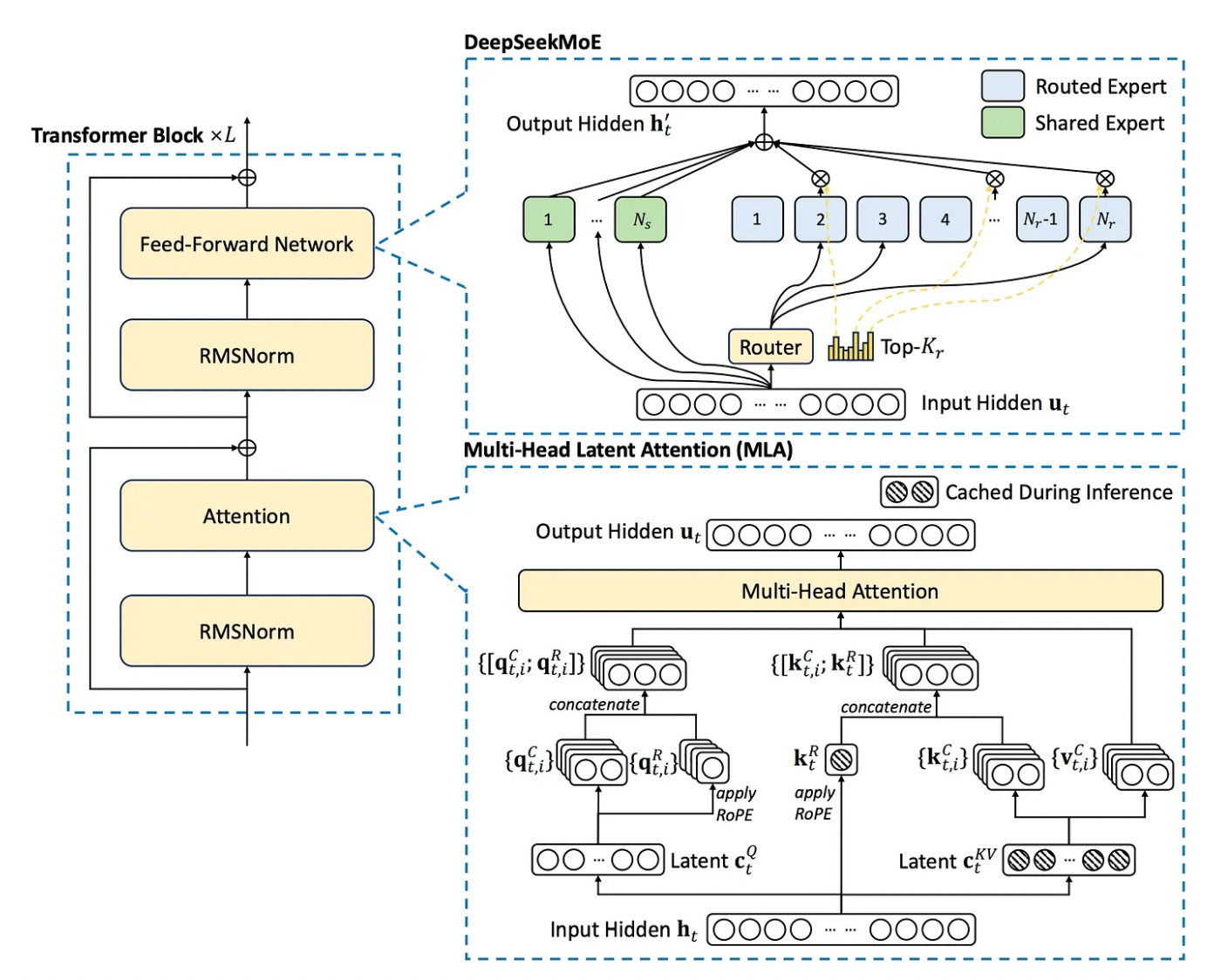

First, a Mixture-of-Experts (MOE) architecture was used. This is not a new approach, and was discussed in my earlier AI (In)Efficiency post, but DeepSeek implements more granular specialization of experts and and optimized routing strategy to minimize communication cost. Second, it uses Multi-head Latent Attention which enhances previous Multi-head Attention with a compressed Key-Value cache that greatly improves inference efficiency. The following diagram is taken from the Deepseek v3 Technical Report.

Deepseek MOE

As mentioned above, Deepseek MOE employs a large number of very specialized routed experts along with a small number of shared experts to handle common baseline knowledge and reduce redundancy among the routed experts.

All MOE architectures balance tokens among experts, to avoid a few experts handling a disproportionate share and becoming bottlenecks. In Deepseek, routing has been optimized by balancing not just based on the token based expert (as is standard for MOE), but also device and communication balancing. Specifically, the routing load balancing takes into account:

the expert based on the input tokens, as in standard MOE

device level balancing, to ensure balanced communication to all devices, each of which runs multiple experts

communication based balance loss to take into consideration the volume of data (number of tokens) routed to each device, not just the number of communications

Multi-Head Latent Attention

It is common for transformer based large language models to implement Multi-Head Attention (MHA), which basically examines the same input (head) multiple times in parallel with different weights, then combines the multiple outputs. This can lead to a better output, but at the cost of multiple key-value (KV) pairs and so a larger KV cache.

There are existing methods to reduce the KV cache size, but at the cost of model performance.

DeepSeek innovated a low-rank joint key-value compression, Multi-Head Latent Attention (MHLA), significantly reducing the size of the KV cache while maintaining, even in some cases improving, performance. The critical innovation here is the “joint” compression, which optimizes for a joint objective that simultaneously optimizes for factorization error and model performance (see Lossless Model Compression via Joint Low-Rank Factorization Optimization).

s1: Simple Test-time Scaling

This approach seeks to improve inference and reasoning performance by increased test-time computation. It does so using a small (only 1000 samples) but carefully curated test set. In addition, the approach applies a constaint on the minimum number of tokens (to ensure quality) and also maximum number of tokens (to control compute), which the authors call budget forcing. In addition, the approach demonstrates the ability to scale inference time performance with increased test time, with important limitations.

Test Set Curation

Starting with a test set size of about 60,000 samples collected from a diverse set of source datasets, the samples are then wittled down based on quality, difficulty and diversity.

Quality - remove samples with poor formatting, errors in accessing, inconsistencies.

Difficulty - two open source models, Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct and Qwen2.5-32B-Instruct are evaluated on the test samples. If either of those models can solve the test sample problem, the sample is considered too easy and removed.

Diversity - classify the remaining test samples into domains defined by the Mathematics Subject Classification system (which includes science domains as well as different branches of mathematics). 1000 samples are then chosen by choosing domains randomly and then taking a sample from that domain that weights difficulty (defined by a longer reasoning trace.

Budget Forcing

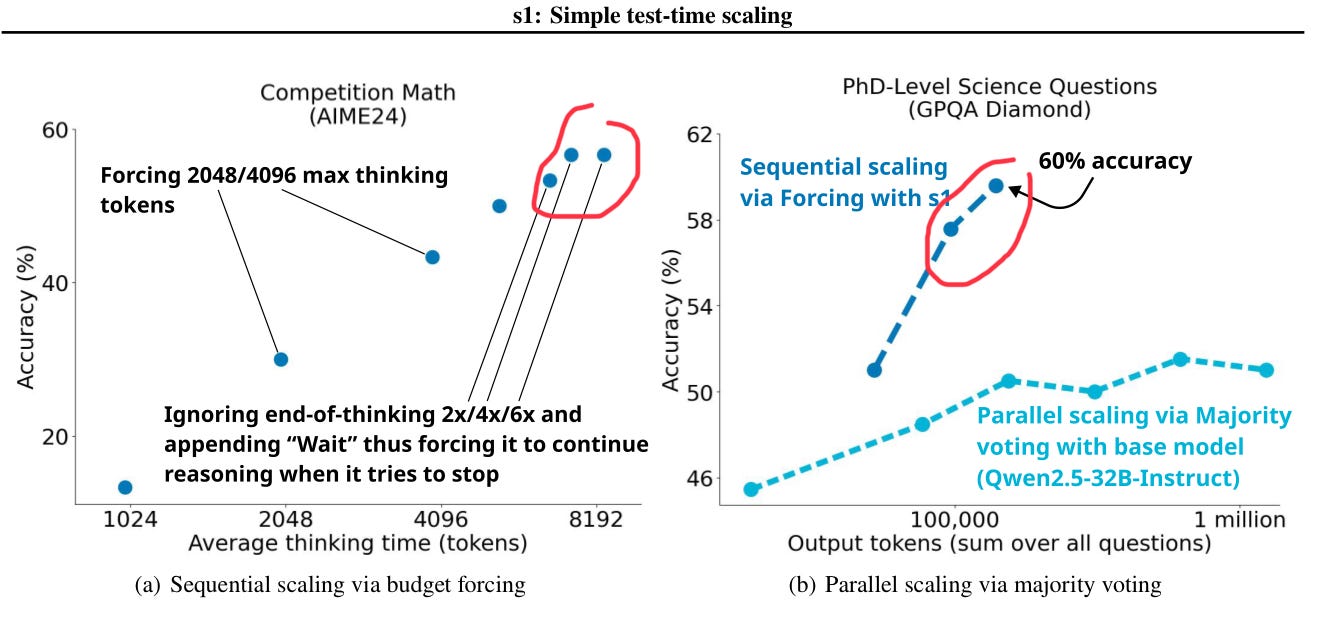

The approach is very simple - a maximum token count is enforced by appending the end-of-thinking token delimiter and string “Final Answer:” to stop computation, while a minimum token count is enforced by suppressing the end-of-thinking token delimiter and/or appending the string “Wait” to trigger the model to continue computation and come up with a better solution.

Test-time Scaling

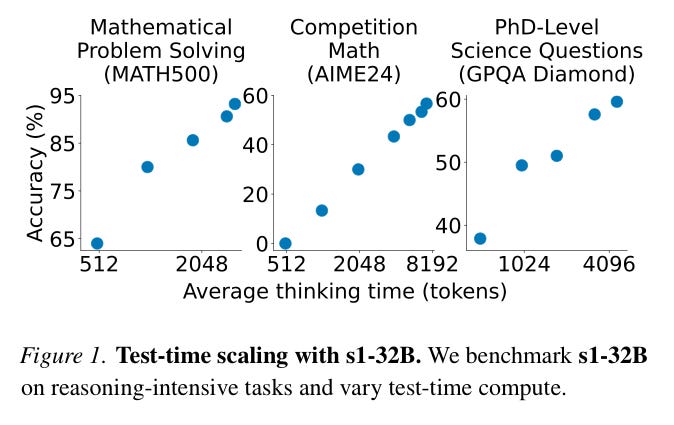

Up to a point, increasing test time also increases model performance. In the following figure from the s1: Simple test-time scaling paper, the more or less linear (suitably normalized) scaling is clear as average thinking time increases.

However, as seen in the following diagram from the s1: Simple test-time scaling paper, one can see at the upper right of each chart (circled in red) that scaling flattens out at the highest accuracy achieved. The maximum context window supported by the underlying model also constrains scaling.

The authors suggest possible future research directions to get past these limits - different methods of extending computation, use of reinforcement learning in concert with budget forcing, and parallel scaling.

Conclusions?

Innovative for sure, and a significant improvement in efficiency with little to no performance degradation, but DeepSeek still relies on a pretrained foundation model. Since open source, the cost of that pretrained model can be reused, in a sense amortized, across many applications. But the foundation model training cost is not avoided.

Similarly, s1 optimizes test-time scaling, but again only after a pretrained foundation model is ready. But by addressing inference/reasoning performance, which will become more and more the issue as opposed to training, test-time scaling promises to be an important approach. Although given the current limitations on that scaling, more work is needed.

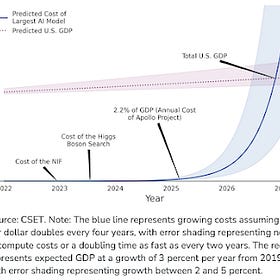

These are valuable innovations, but on their own these innovations do not resolve the compute resource trends in training and using LLMs.